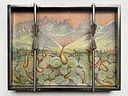

Animals do not appear in Alina Blyumis's latest episode of "Zoo Pictures"; the spectators themselves are imprisoned in the cage. The watercolor paintings depict imaginary, paradisiacal landscapes of lush greenery, palm trees and flowers drenched in soft light, on wood panels framed by steel redolent of prison bars, cages and fences. By juxtaposing idyllic scenes of nature with the apparatus of limitation and exclusion with which people “drive themselves into a zoo,” Blumis draws attention to the state of alienation in which we live.

The series' subtitle refers to the island of Nauru, nicknamed "Pleasant Island" by a British sailor in the eighteenth century. The island's troubled history reflects the global problems depicted in these paintings: European phosphate companies mined the island throughout the twentieth century, leaving behind, as National Geographic photographer Rosamond Dobson Rhone wrote in 1921, "a bleak, terrible tract of land with a thousand towering white corals vertices"; After 800 million tons of phosphates, Nauru has lost 80% of its original vegetation. Since 2001, it has housed detention centers for migrants seeking asylum in Australia and has been the subject of numerous human rights complaints.

In this context, fences, boundaries and cell walls take on new meaning, literal and figurative. These physical divisions signify ownership, not control, of land. Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that our political communities are structured on the basis of such a division: “The first man who, having fenced off a piece of land,” he wrote, “said: “This is mine,” and found people naive enough to believe him that this man was the true founder of civil society." Now, according to some estimates, the total length of fences in the world is ten times the length of roads.

The series invites the viewer to reflect on the false boundaries established between people and the environment, as well as between political communities. Nauru is a microcosm of the complex interweaving of these two trends—ecological destruction on the one hand and border violence on the other. Through these images of paradise and the stark metal bars that separate the viewer from our landscape, the series hints at the possibility: What if we tore down the fences?

-thumb.jpg?alt=media&token=5e9ae36a-a7ea-44cd-8765-81a253749759)

ruhi-i-mizhnarodny-pospeh_-vyniki-goda-%D1%9E-mastactve-%E2%80%94-reform.by-thumb.jpg?alt=media&token=4644da18-2e31-44ff-b733-10da53b0a833)

-thumb.jpg?alt=media&token=75e9a684-08cb-4915-8abf-b523c9c127ea)