Weakness Street

29 IV 2022 – 19 VI 2022

Venue: Günter Grass gallery in Gdańsk (Poland)

Artist: Lesia Pcholka

Curator: Anna Łazar

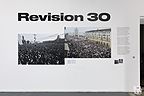

Lesia Pcholka’s exhibition at the Günter Grass gallery in Gdańsk is an attempt to face the experience of the Belarusian civic uprising after the fraud in presidential elections and resulting repressions. The artist worked on her exhibition for more than half a year; meanwhile Russia invaded Ukraine. Ukraine is fighting back, its civilians being ruthlessly murdered by Russian soldiers. Moral and legal evidence of the genocidal character of Russian activities is growing. Still, the Belarusian trauma has not ceased, the overwhelming majority of the political prisoners have yet been released, many people are in exile, but the propaganda is working at full speed.

Lesia Pcholka' “Weakness Street” is muted. The artist tries to find the means to express processes which are difficult to grasp and which pertain to the relationships between governmental administrators and Belarusian society. These relationships have even ceased to be based on oppressive laws, reaching instead the stage of violence and terror. What can a representation of such relationships be? Films, photographs, witness accounts, images of beaten-up people are certainly within the artist’s scope of activity; however, for the needs of the exhibition, Lesia creates an installation referring to seemingly neutral objects which can be encountered during a walk. She shows newspaper and flag holders, along with the decorated bases of street lamp posts in a central street of Minsk, which have witnessed many a renaming of the street where they have stood for decades. By the title of her exhibition, the artist makes a proposal adequate to the current time. These alienated objects – perhaps with the exception of the lamp post base, which falls out of the association line with “propaganda tools”, still refer to the continued experience from the times of the USSR – they have become the sign of a frozen public space, a space prepared to perpetuate the message of power. Amidst oppressive architecture, between newspapers with their virulent messages, there are portraits of people who want to give vent to their beliefs despite the threat. They are photographs made using applications covering the faces of those who are protesting but have to protect themselves against the retaliation of power. The mask has the shape of an A4 sheet of paper. This simplest, universal shape became the symbol of protest. White sheets of paper were hung out in the windows when repressions for displaying flags were increasing.

Lesia Pcholka’s art does not serve any propaganda, nor does it try to lecture on what the construction of a totalitarian state is like; however, it is the utterance about the social mood in Belarus built in the field of art. This is not an easy exhibition. Because the experiences of our neighbours are not simple. When we open ourselves up to their stories we not only demonstrate solidarity, but also acquire knowledge. The mechanisms which have been applied in these parts of the world which seem distant, have permeated unnoticed to the places we consider close.

Anna Łazar

Sasha-Velichko-(1)-thumb.jpg?alt=media&token=53e8f1c7-85c7-41a9-bce4-f1cd3dd6d28c)